Black Bart

Charles Earl Boles, better known as Black Bart, stood quietly hidden among the dense California trees, his eyes fixed firmly on the approaching Wells Fargo stagecoach. It was 1882, and by this point, Black Bart had solidified his status as the most intriguing and unconventional outlaw in the American West. Unlike his contemporaries, Bart was neither violent nor impulsive. Instead, he conducted his robberies with calculated politeness and poetic flair.

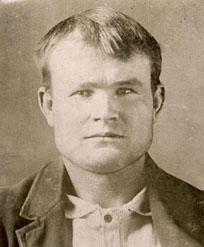

Dressed impeccably in a long linen duster coat and topped by a stylish bowler hat, Black Bart looked more like a refined gentleman than a highwayman. His face partially concealed by a simple flour sack mask with eyeholes cut out, he presented an enigmatic figure—calm, controlled, and unfailingly courteous.

As the stagecoach rounded the bend, Bart stepped calmly into view, a shotgun resting comfortably in his arms. "Driver, kindly halt your horses," he called out politely, his voice firm but friendly.

The startled driver pulled sharply on the reins, bringing the coach to an abrupt stop. "Easy there," Bart assured gently, noticing the driver's nervous hands. "No one needs to get hurt. Just toss down the strongbox."

The passengers peered curiously from the coach windows, surprised and somewhat amused by Bart’s gentlemanly manner. Without argument, the driver complied, dropping the heavy box onto the dusty trail below.

"Thank you kindly," Bart said cordially. "Please extend my regards to Wells Fargo."

Before disappearing, he tucked a neatly folded piece of paper beneath a small rock near the road. With a courteous tip of his hat, Bart vanished swiftly into the trees, leaving behind only mystery and intrigue.

Hours later, when authorities arrived, they found the poem Bart had carefully placed. The verses, playful yet mocking, served as his unique calling card, capturing imaginations far and wide:

"I've labored long and hard for bread,For honor and for riches,But on my corns too long you've tread,You fine-haired sons of bitches."

Wells Fargo detectives fumed, both frustrated and amused by Bart’s audacity. Despite their best efforts, Bart continued to evade capture, executing robberies with almost theatrical precision. He rarely spoke harshly, never harmed a soul, and never fired his shotgun, which was later revealed often to be unloaded.

Born in 1829, Black Bart was an English immigrant who arrived in California during the Gold Rush, initially seeking fortune in the mines. But when prospecting failed to yield wealth, he turned to robbing stagecoaches. Unlike other bandits, Bart operated alone, meticulously planning each heist, choosing isolated locations and always maintaining civility. His careful preparations and precise timing allowed him to escape undetected each time.

His legendary status grew with each robbery, as newspapers sensationalized his exploits, dubbing him "the gentleman bandit." Public opinion split sharply—some admired his style and panache, while others condemned his criminal acts.

Bart’s career as an outlaw spanned eight years and at least twenty-eight robberies. Yet despite the frequency, he remained elusive, living quietly in San Francisco between robberies, blending seamlessly into high society under his true identity as Charles E. Boles.

However, even the most careful outlaw eventually slips. In November 1883, Bart robbed a Wells Fargo coach near Copperopolis, California. During his hasty escape, he inadvertently left behind a handkerchief marked with a laundry identification number. Detectives swiftly traced the item back to San Francisco, finally unveiling the outlaw’s true identity.

Detective James Hume apprehended Bart, arresting him without incident at his modest boarding house. When questioned, Bart calmly admitted to his crimes, expressing relief that his outlaw career was finally over.

Convicted and sentenced to six years in San Quentin Prison, Bart served four years, his behavior exemplary and polite, befitting his gentlemanly image. Upon his release in 1888, he vowed to leave crime behind.

Yet, strangely, Black Bart seemed to vanish completely after prison. Some speculated he moved east, living quietly under an assumed name. Others believed he returned to England, his birthplace, to spend his remaining days anonymously. Regardless, he never again committed another known crime.

As the years passed, Bart’s story evolved from notorious outlaw to captivating folklore. He became a romantic figure, the embodiment of rebellion against the excesses of powerful corporations like Wells Fargo. Unlike many of his violent contemporaries, Bart was remembered fondly, as much for his poetic wit as for his crimes.

Stories about Black Bart spread far beyond California’s gold country. People marveled at the refined, polite robber who used words rather than bullets, whose crimes seemed more theater than threat.

Black Bart’s legacy endured precisely because he defied expectations, challenging the stereotype of violent frontier outlaws. His life highlighted the contradictions of the American West—a place where a polished gentleman could become a legendary criminal, capturing imaginations through poetry and politeness rather than brute force.

Black Bart, the poet outlaw, remains one of the Wild West’s most fascinating characters, forever etched into history as a mysterious figure who chose wit over violence, style over savagery, and courtesy over cruelty.